Choosing Your Team: Experience, Expertise, and Ego

By Alison Levine, Tuesday, March 28, 2017

On expeditions where teams face danger on a daily basis, climbers literally put their lives in their climbing partners’ hands, so you better choose your team wisely. Recruiting mistakes can be costly. We’re not talking about the difference between winning or losing market share—we’re talking about life and death.

In extreme environments when everyone is feeling stress, there is no employee handbook you can reference to figure out how to deal with difficult people. Dr. Phil is not going to show up to counsel you on the proper way to handle people who aren’t working well with others or are more concerned with themselves than they are with meeting team goals. That’s why you must choose your partners wisely, be it in business, life, or sport.

I knew there was a lot at stake when I first started recruiting members of the first American Women’s Everest Expedition in 2002. I also knew I needed help, because at the time I just didn’t know that many female climbers who would be both interested in and qualified for an Everest climb. I contacted everyone whom I had ever climbed with in the past and asked them to reach out to their networks in order to help me compile a list of names and climbing résumés. Naturally, I was immediately drawn to the women who had the beefiest climbing bios—women who had climbed the most mountains, the highest mountains, the toughest mountains. But I realized very quickly that it wouldn’t do me any good to be high up on a mountain with the world’s most elite climbers if they didn’t care about the rest of the team. I also realized that I didn’t want to be up there with people who were just fun and cool and easy to get along with if they lacked the necessary skills to survive and succeed in that environment. When you’re taking on a big mountain, you have to find people who are the perfect mix of skill, experience, and desire. And not just the desire to climb, but the desire to be team players.

I wasn’t looking for women who just wanted to scale Everest—I needed athletes on the team who would embrace the experience of climbing with other women and who would be proud to wear the American flag on their jackets. And then there was the question, Would I trust this person with my life? If the answer was yes, then I had to ask myself, Is this someone with whom I would want to spend two months in a tent?

Our sponsor, the Ford Motor Company, set some other requirements for team members that knocked some fabulous women out of the running, but their recruiting guidelines made perfect sense to me. The team members had to be American, they had to be women (after all, it was the first American Women’s Everest Expedition), and they could not be professional climbers. Ford didn’t want the team to be comprised of professionals, because they were creating a PR campaign focused on sending a message about pushing your limits, challenging yourself, and getting outside of your comfort zone—which meant doing something that required you to stretch. Of course, climbing big mountains can be a stretch for professional climbers and full-time mountain guides, but it’s something they get paid to do frequently. That was why Ford decided they wanted the team to be “regular women” who were strong mountaineers but who didn’t do it for a living. Ford dubbed the project “Team No Boundaries,” which went along with the “No Boundaries” ad campaign for their SUVs back in 2002. They wanted people to look at our team and say, “Hey, if those ladies are climbing Everest, then maybe I can [fill in the blank].”

There wasn’t enough time or money to interview prospective teammates in person, so I had to decide who would make the final cut based solely on phone interviews (we didn’t have Skype back then). But the process proved to be easier than I anticipated. It usually didn’t take me more than a few minutes of conversation to know if I wanted the person on the other end of the line to join the team. It wasn’t hard to tell which of them were going to be good team members and which might not be as good a fit. Some women asked questions like “How much are we getting paid?” or “Are we flying first class?” “Nothing” and “No” were the answers to those questions. I worried that these women wouldn’t be the best fit for our team, because they seemed more interested in money and perks than in the opportunity to be part of something really special—something that would happen only once in a lifetime. But other women asked questions like “What can I do to help? Can I help raise funds for the trip?” or “Even if I am not selected to be a part of the team, can I pay my own way to base camp and cheer you on from there? Can I design a website for you? What can I do to be part of this team if I am not given a spot on the actual climb?”

This was precisely the kind of upbeat response I wanted to hear. You’re in! Alfred Edmond Jr., the senior vice president and editor at large of Black Enterprise, once shared some advice with me on the subject of recruiting talent: “Screen for aptitude, then hire for attitude.” Looking back on my recruiting process in 2002, I realize I was doing just that. I had pooled names of all the candidates who had the skills to climb a monstrous mountain, and then made my choice based on who had the best attitude.

Joining me in Nepal for the first American Women’s Everest Expedition were Jody Thompson, Kim Clark, Lynn Prebble, and Midge Cross. Jody, Kim, and Lynn were from Colorado, and Midge was from central Washington. All were talented outdoor athletes. We ranged in age from thirty-five to fifty-eight. Our backgrounds were completely different, but the one thing we all had in common was a passion for climbing mountains. And while none of us were professional climbers, the five of us had more than one hundred years of cumulative climbing experience between us. Interestingly, all but one of us had overcome some type of health challenge. I have had a few heart surgeries and suffer from Raynaud’s disease, Midge has diabetes and is a breast cancer survivor, Lynn has osteoporosis and exercise-induced asthma, and Jody had developed HELLP syndrome, a life-threatening condition that occurs during pregnancy, and nearly died in childbirth. Her son Hans had to be delivered three months early and weighed a mere 1.5 pounds.

Accepting a spot on the team meant Jody would be leaving Hans, then eleven months old, for eight weeks while she was in Nepal. She later said that it was one of the hardest decisions she ever had to make. The fact that she had a supportive husband, Mark, who said, “Go! I’ll figure out how we’ll manage back at home,” is what pushed her over the fence. Mark, an attorney and also an avid climber, realized this was an incredible opportunity for Jody and didn’t want her to miss out on the experience. (This is an example of someone who chose her life partner wisely.)

Ford brought our entire team together for the first time during a photo shoot in Breckenridge, Colorado, about a month before we left for Nepal. It was great to have the opportunity to finally meet everyone. Ford also sent out its PR team from Hill & Knowlton to spend a few days with us in order to manage the photo shoot and help us prepare for our upcoming media tour.

The Hill & Knowlton folks filled us in on what would be expected of us during our scheduled television appearances, which would take place in New York the week before we headed off to Everest. They helped us prepare by going over messaging and conducting mock interviews so we would be ready when we were actually live on camera. Talk about getting out of your comfort zone. We were probably more nervous about our upcoming television appearances than we were about the climb. We also spent a good portion of the weekend posing for photos for the PR campaign. We even staged a ladder crossing to look like the Khumbu Icefall. And of course we took photos with the then-new 2003 Ford Expedition, which, you should know, is the only full-sized SUV with independent rear suspension and optional third-row power fold seats—or at least it was at the time (hey, gotta plug the sponsor)!

During those two days in Colorado the team seemed to have good chemistry, so that was reassuring. We got to know each other, and we spent a lot of time talking and laughing and sharing our excitement and our fears about the challenges that lay ahead for us in Nepal. But we were in a comfortable environment with all the amenities we were used to at home (running water, toilets, showers, good food, and a thermostat to control the indoor temperature). How would this team fare on the highest mountain in the world in some of the most extreme circumstances that human beings ever face? How would we do when it became painful and uncomfortable and our bodies were being pushed to their limits? People can put up with just about anything for two days. But we were looking at two months together. With all the uncontrollable factors you have to deal with on a big mountain, the last thing you want to have working against you is team dynamics.

So how’d it work out? Well, let me say this: If I had to pull together another team of women, I would pick the exact same ladies (plus a few others I have climbed with in recent years). Every woman on that team was truly grateful for the opportunity to be there and behaved accordingly. They got a free trip to Everest, courtesy of Ford, and they were incredibly grateful for that. I don’t think there was a single day when someone didn’t mention how lucky they felt just to be on the mountain.

From the very beginning this group felt like a team. Even before we got to base camp we talked about the expectations we needed to meet—for each other and for our sponsor. We approached everything from a team perspective. We climbed together, obviously, but even during the downtime on our rest days we spent time strategizing about how we were going to approach the various challenges that were awaiting us higher up on the mountain. At one point we even made a pact that on summit day, if one person needed to turn around before we reached the top, the entire team would turn around with her. We wanted to send a strong message about solidarity and the bond among us and that this was more important than the top of a mountain. Climbing is often known as a selfish sport, and we wanted to shatter that myth.

We actually ended up scrapping that plan, because despite our best intentions, that type of strategy could have been detrimental. We were afraid that it might cause someone to push herself further than she should—past her limits to the point where it could be dangerous—because she didn’t want to be the one who made the whole team turn around. That’s how people die on Everest—they push themselves so hard to get to the top, and then they have nothing left to get themselves back down. We didn’t want that to happen to anyone on our team. So in a sense, changing our mind was another expression of our bond.

There was not one time during the expedition when we didn’t get along, which is actually very unusual. When you’re with people 24/7 in isolated, extreme environments, it’s completely normal for people to grate on each other’s nerves and for tension to arise among team members. But not on this trip. Everest climbers who read this may roll their eyes—Aw, c’mon! But I am telling the truth here. There was virtually no conflict among our team members. I kept waiting for things to go south. It never happened. There were no divas. There were no selfish climbers. Now, that’s not to say that there wasn’t conflict with others—those outside of our immediate team. With a big expedition there are a lot of folks involved in addition to the climbing team (logistics managers, base camp managers, communications managers, guides, etc ). Conflict is, of course, a predictable component of group dynamics, and it can actually be healthy.

Conflict becomes dangerous only when it is unresolved. That’s when it can be destructive. When you’re in an extreme, isolated environment and people start behaving badly, you can’t threaten someone by telling them that they’ll be written up and a note will be put in their permanent file. You have to find ways to minimize people’s crappy behavior as well as the impact of that behavior—and you have to do it right away. That means bringing the conflict out into the open, where you have a shot at resolving it. Communication is key. It’s essential to make sure that each team member knows that he or she is valued and that his or her opinion matters.

When I speak to various organizations about leadership and recount the details of the expedition—including my admiration for my team—I am often asked what made that team of women so great. I always used to respond with, “I don’t know—that there was just this magic chemistry among the five of us.” I would tell people that the women were all very easy to get along with, low-maintenance, appreciative of the opportunity, and incredibly considerate of each other and of the other folks involved with the expedition. I kept telling people, “I just got really lucky with the team.”

It wasn’t until October 2012, more than ten years after the expedition, that I realized why it was that our team was so special. I was at Duke University for our annual board meeting of the Fuqua/Coach K Center on Leadership and Ethics. Coach K (full name: Mike Krzyzewski) has been the head men’s basketball coach at Duke for more than three decades. He had recently come back from winning gold as the head coach of the United States men’s national basketball team at the Olympic games in London. Over breakfast that morning he shared with us his process of choosing the players for the US team. He said that one of the things he looks for in players is ego. He wants them to have it, and plenty of it. I thought, Huh??? You want ego? Doesn’t that go against everything I’ve ever read or have been taught about the kinds of people who make good team members?

Coach K went on to explain that when you are trying to put together a high-performing team, you want people who are good and who know they’re good—because that gives them the confidence to know they can win. Coach K calls it performance ego. Of course his team included Kevin Durant, Kobe Bryant, and LeBron James—three of the best players the game has ever seen. They had every right to have big egos. After all, stats don’t lie. Coach K said he absolutely hates the phrase, “Leave your ego at the door.” He wants his players to exude confidence and to be who they are; he does not want them to rein it in. “I don’t want LeBron James to walk into a room and be a wuss,” he told us. (Actually, I don’t think Coach needs to worry about that.)

Having a strong ego doesn’t mean you’re disrespectful of others, because you can bet that Coach K wouldn’t put up with that. He has a list of standards that he expects from all of his players, college or pro:

- Look each other in the eye.

- Tell each other the truth.

- Never be late.

- Don’t complain.

- Have each other’s backs.

Coach went on to tell us about the second type of ego he wants and needs in his players—and that’s team ego. He wanted everyone playing for him to feel extreme pride in being part of Team USA, and they did. For everyone involved it was about the opportunity to represent their country on the court. It was about national pride, not individual pride. It was an opportunity to be part of something truly unique that would bring together the best in the sport from all over the world. No one got paid to play on the US basketball team. They played for two months in the summer, then rejoined their NBA teams in September for training camp prior to the regular season, which started in October. So during the summer they were away from loved ones, they were risking injury, they were not getting paid—and they were doing it for the team—the chance to be a part of something that was greater than the sum of its parts.

Climbing is a sport that is also filled with big egos. Prior to listening to Coach K, I used to think a big ego was a bad thing, but I was confusing ego with arrogance. Coach K’s ideas about egos made perfect sense to me. If you’re going to put together a team to take on a big mountain, you want people who have what it takes and who know they have what it takes. You want them to think they’re great at what they do. You don’t ever want to climb the Hillary Step (one of the most technically demanding parts of the route) behind someone who, at 28,740 feet, is thinking, I don’t really know if I have what it takes to do this. People who hesitate on the route cause bottlenecks, and this is a serious issue up in the death zone. Anything that slows climbers down is dangerous, because it increases the chances that something will go wrong. Climbers need to keep moving in order to generate enough body heat and energy to keep their extremities and organs alive. You can suffer hypothermia, frostbite, or maybe something worse from standing around in the cold on an exposed section of the route. You can even run out of oxygen. When that happens, people can die.

You want people on your team who look at the toughest parts of the route and just know they can crush it. (I’m talking justified confidence; self-delusion is a whole different story.) You don’t have to actually enjoy all the hard parts (there were plenty of spots on Everest that I didn’t like), but you have to be good enough to get past them and you have to have confidence in your abilities to do so.

After thinking about Coach’s words, I realized that what made our team great wasn’t luck or some kind of crazy magic (as I had been telling people for ten years)—it was simply a matter of ego. Those women had performance ego; more important, they had team ego. They were grateful to be a part of the first American Women’s Everest Expedition. They were constantly thanking me for giving them the opportunity to take part. They kept talking about how indebted they felt to Ford for funding the trip and making it possible for us. They realized that they were part of something really special. Like the US Olympic basketball team, we weren’t getting paid for our efforts (we were actually taking a financial hit because we were each forgoing two months’ salary). We were going to be away from loved ones for a long time (sixty days), and then, as soon as we returned, we had to go back to our old jobs and hit the ground running. (I was at my desk at 6:00 the morning after I returned from Nepal.)

But that unique sense of team ego eclipsed the concerns about any of those things because we were hugely proud to be on that mountain as a team of American women. Sending a message about pushing your limits and getting outside of your comfort zone resonated with us, and that further strengthened our bond. It helps to believe that your purpose and mission are meaningful. And while our Everest team did not make it to the summit in 2002—we missed it by just a couple hundred feet due to a storm—it was the biggest honor of my life to have had the opportunity to be part of that expedition. It wasn’t about the summit. It was about the team.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “a team” as “a number of persons associated together in work or activity.” I vehemently disagree. Just because you have a group of people doing the same thing at the same time—even if you have the same goal (like climbing a big peak)—it doesn’t make you a team. It just makes you a group of people doing something at the same time. A group is only a team when every member of the group cares as much about helping the other members as they care about helping themselves.

Alison Levine

Alison Levine is a history-making polar explorer and mountaineer. She served as team captain of the first AmericanWomen’s Everest Expedition, climbed the highest peak on each continent and skied to both the North and South Poles—a feat known as the Adventure Grand Slam, which fewer than forty people in the... Read More +

Alison Levine is a history-making polar explorer and mountaineer. She served as team captain of the first AmericanWomen’s Everest Expedition, climbed the highest peak on each continent and skied to both the North and South Poles—a feat known as the Adventure Grand Slam, which fewer than forty people in the... Read More +

"The fear of failure is the main factor that prevents people from taking risks, which is unfortunate. I think it's good to fail at times. When you don't achieve the goal you set out for yourself, you can still learn from that experience."

Alison Levine

More +

"The fear of failure is the main factor that prevents people from taking risks, which is unfortunate. I think it's good to fail at times. When you don't achieve the goal you set out for yourself, you can still learn from that experience."

More +

"The fear of failure is the main factor that prevents people from taking risks, which is unfortunate. I think it's good to fail at times. When you don't achieve the goal you set out for yourself, you can still learn from that experience."

Choosing Your Team: Experience, Expertise, and Ego

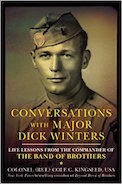

Conversations With Major Dick Winters (Life Lessons From The Commander Of The Band Of Brothers)

Colonel (Ret.) Cole Kingseed

Colonel (Ret.) Cole Kingseed